The Worm Is (Slowly) Turning

Hi everyone,

I kept this out of the monthly update because it’s a bit longer, and I wanted to provide a more in-depth discussion on this topic.

While most of the world was focused on the Federal Reserve and the general craziness of the world. A couple of remarkable things have been happening in the world of energy recently.

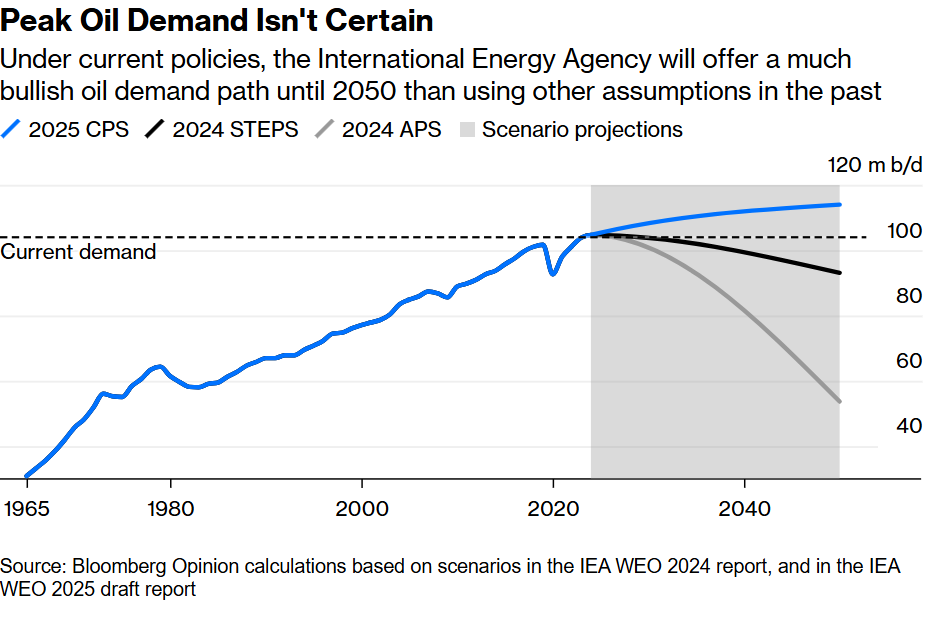

Two weeks ago, the IEA (International Energy Agency) admitted what has been obvious all along. That peak fossil-fuel demand is nowhere in sight.

Just as a refresher, what is the IEA? It’s the Paris-based global energy research organization that was founded in the 1970s to help coordinate energy policy between developed countries to avoid another oil shock.

It has been one of the major reputable sources of information and forecasts on global energy supply and demand for decades. But over the last ~5 years, it became completely consumed by climate change and net zero.

This was the organization that famously said “there can be new investments in oil, gas and coal, from now - from this year” in 2021.

Even if the energy industry rolled its eyes and knew how deeply unserious the claims were. The IEA has still retained its reputation as a world-renowned energy organization. Its reports and projections are routinely quoted in the media and have a significant impact on markets and broader perceptions of the energy industry (and its future prospects).

So the U-turn when the IEA admitted that demand will continue to grow, possibly for decades, was quite the shock to everyone.

This shouldn’t be surprising.

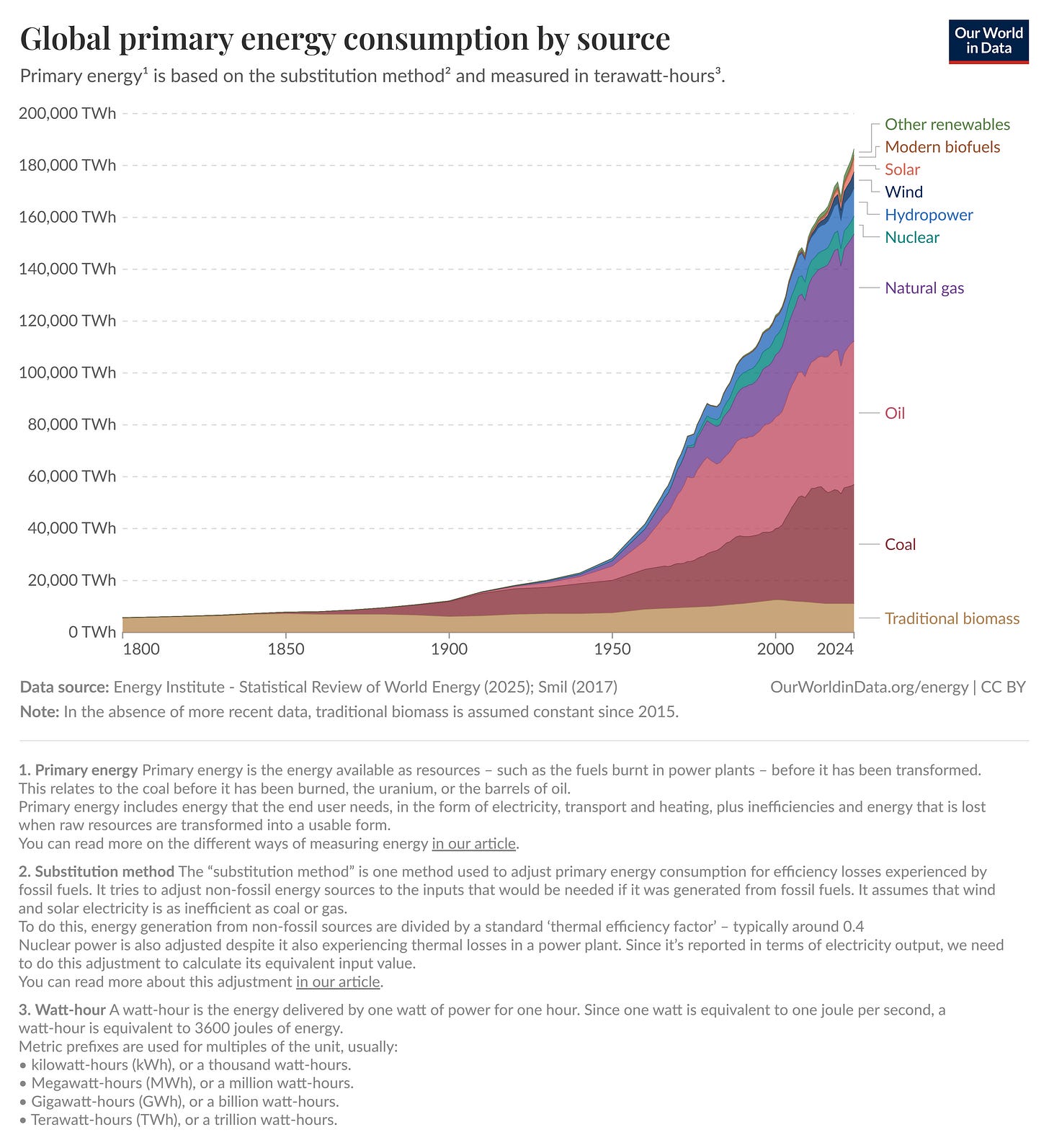

As I’ve written in the past, we aren’t living through an “energy transition” phase but an “energy addition” phase.

The world is consuming record amounts of biomass (grass, wood, animal dung, etc., which somehow got the label as green & renewable, but that’s another story).

The world is consuming record amounts of coal.

The world is consuming record amounts of oil.

The world is consuming record amounts of natural gas.

Even as the world continues to build out more and more solar and wind.

This quote from Mark Twain perfectly encapsulates fossil fuels:

"Rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” -

Finally, the IEA is coming to its senses when reality was just too hard to ignore.

But it doesn’t stop there. The IEA last week published another new report, this time0 on the supply side.

Too often, the focus of energy research is on the demand side while the supply side is ignored. Largely due to the rapid growth of the US shale industry over the last decade. Which has accounted for over 100% of net oil production growth (thus has making it largely redundant).

The whole report is ~70 pages and very (and can be found here), so I’ll do my best to highlight some things that I found interesting.

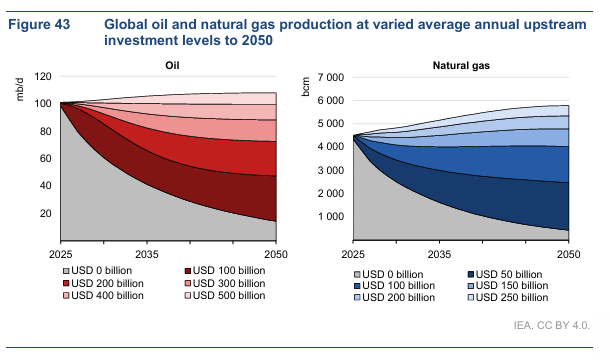

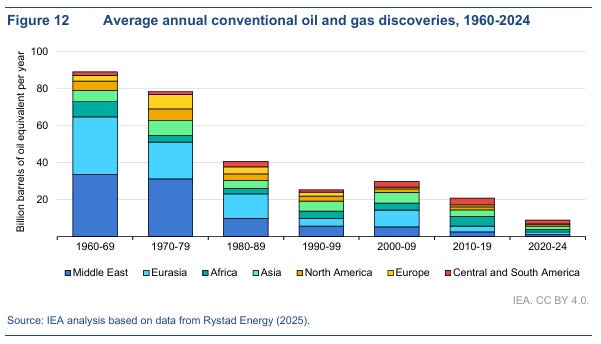

The most important point is that the IEA estimates that since 2019, 90% of capex spending ($500 billion out of $550 billion) has gone towards replacing depleting oil production (i.e. maintaining production).

And it gets worse, due to global decline rates which are now at 8% (more on that in a bit). The IEA now estimates that capex will have to be in excess of $540 billion just to maintain current production levels.

But here’s the rub. We’re now in “budget season” and all of the oil companies are finalizing the capital spending plans for 2026. Oil is now in the mid-60s, the lowest in 5 years, and many forecasts are calling for $50 oil next year.

I have no idea what the national oil companies will do, but it’s all but certain that the private companies (NOCs and privates each make up roughly half of capex) will be cutting spending again for 2026. Even if the NOCs keep spending flat, Houston we have a problem.

Because the world will be ~$20billion (or more) short on maintaining oil production. And the deficit will get even worse if demand grows.

So let’s circle back to that 8% global decline rate, which is roughly equivalent to ~8mm bbl/d. For comparison sake, the US Permian now produces 6mm bbl/d. Guyana, which gets a lot of attention, has ramped up production to 1mm bbl/d of oil.

The world focuses on the supply growth side stories. But we often ignore all the countries and oil fields that are declining, such as the European North Sea, Mexico, Venezuela, etc.

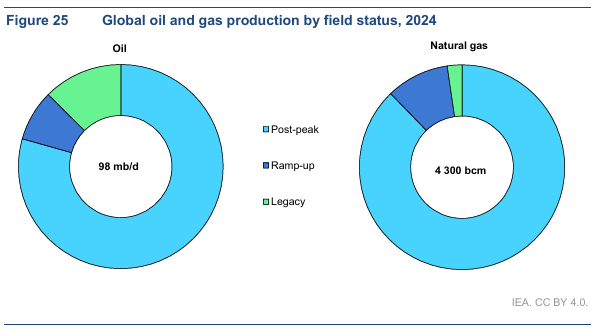

Part of the reason that the decline has risen is due to the rise of US shale (which has decline rates in excess of 35%). Another problem that the world now faces is that, according to the IEA, over 80% of oil production and 90% of gas production come from fields that have passed their peak in production.

And to make matters worse, we already know more or less where all the oil is.

It’s a matter of whether or not it is economical to get it out of the ground. The factors that obviously impact that decision are the price, but also how much it costs, whether technology to extract it exists, geopolitics, etc.

The major problem over the next decade, in my opinion, is that there is no US shale coming to rescue the world this time (unless oil skyrockets).

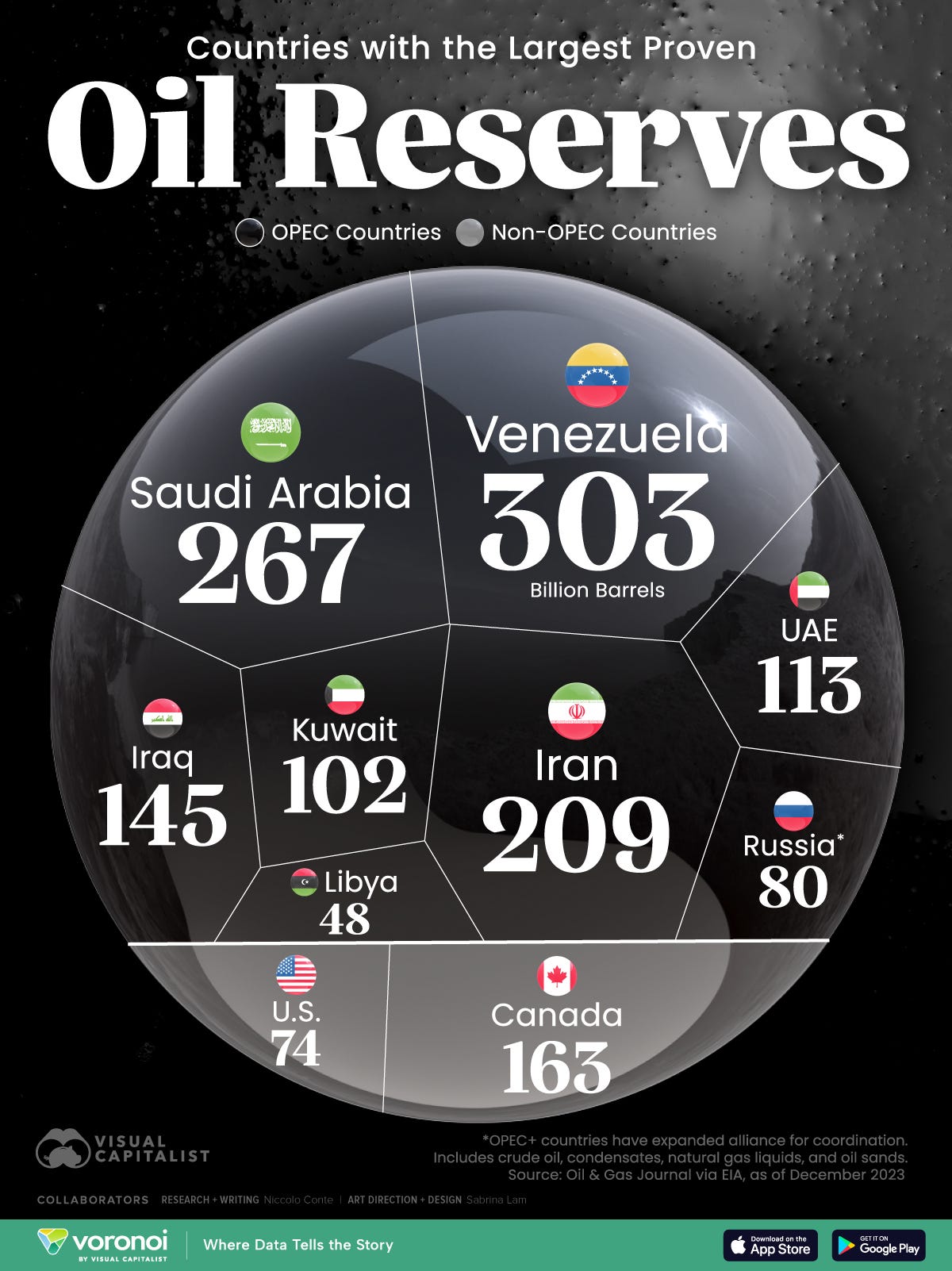

Here’s the list of countries with the largest oil reserves.

There are only two countries (in my opinion) that could materially increase their production out of this group going forward. And that’s Venezuela and Iran. But both countries have serious problems (an understatement).

To give some context, Guyana’s (which again has received a ton of media attention) oil reserves are estimated to be around 11 billion barrels. Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale fields (another media favorite) are estimated to contain around 927 million barrels.

In the grand scheme of things, it’s tiny.

The reason this is all so concerning is that nobody has had to worry about where the next incremental barrel of supply was coming from for the last 10+ years.

Even now, most are still just blindly pencilling in that US shale will continue to grow in perpetuity.

Will it? That’s the trillion-dollar question.

Anyone who has questioned the US shale industry, and especially the all-mighty Permian basin, has been made to look very foolish over the last decade. US shale companies have shown an incredible ability to continually improve and become more productive.

But the Permian basin, which stretches across Western Texas and New Mexico, is showing signs of maturity.

So will it keep growing? Go sideways? Or start to decline?

Let’s have a look at some of the earlier shale fields that predated the Permian.

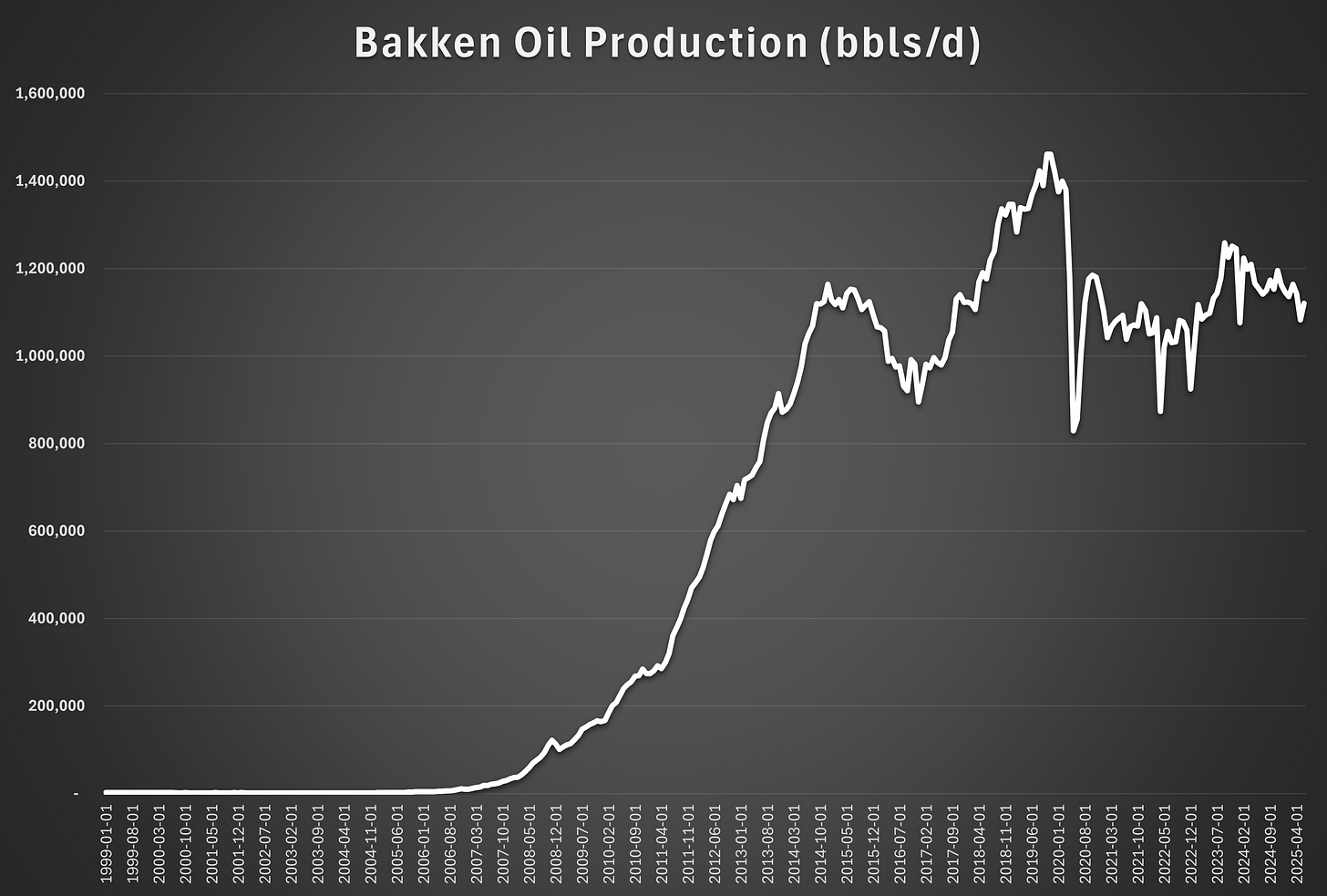

Here’s the Bakken that stretches across North Dakota.

Production soared with the discovery of shale fracturing technology. Dropped temporarily in 2014 when oil prices crashed. Then recovered to a pre-pandemic high at the end of 2019. We saw another small recovery post Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent oil soaring.

But since that peak almost 3 years ago, oil production has slowly drifted down. Current production is now ~23% below the 2019 high and ~11% below its 2023 high with no signs of revival.

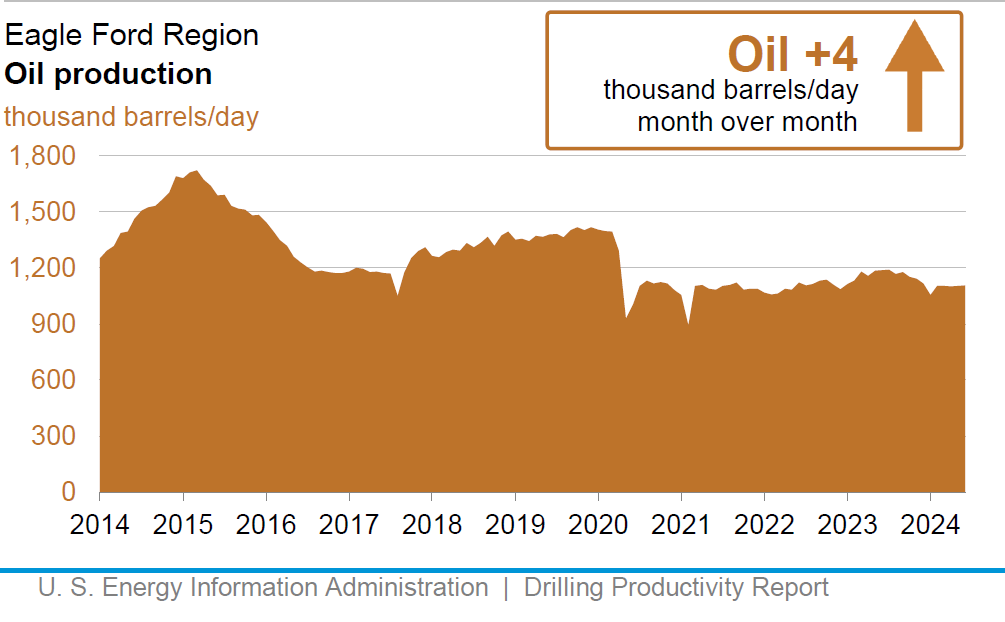

Another example is the Eagle Ford, which snakes across central Texas. It quickly ramped to almost 1.8mm bbl/d in the heady days of the shale boom. But has rolled over to 1.1mm bbl/d and has gone sideways since.

Meanwhile, the Permina might’ve already rolled over, and we don’t (officially) know it yet.

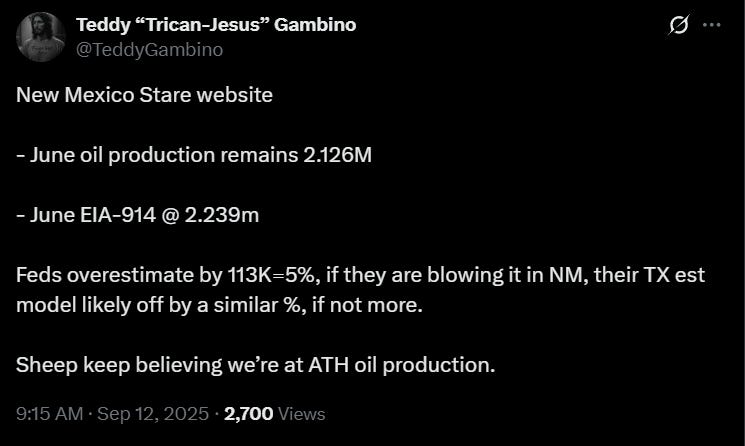

Over on Twitter (formerly known as X), a hedge fund manager noted that EIA’s modelled estimated production for the Permian in New Mexico is about 5% higher than publicly released data from the New Mexico government.

If the EIA’s model for New Mexico is too high. Odds are that the EIA’s model for the Texas side of the Permian is also too high.

Given that the Permian is now half of total US oil production, this is no small matter.

A more fundamental question is where the next Permian is, which went from essentially nothing to 6mm bbl/d over the last 15 years comes from.

But nothing shows how much the worm is turning than what is happening in California. The vanguard of the “clean economy”, climate change, and net zero is making a very humbling U-turn.

Last year, California rolled out an extremely onerous new set of news laws regulating the refinery industry. This was the last straw for many in the industry as Chevron moved its headquarters to Texas and multiple refineries announced they would be shutting down.

California is now facing declining in-state production, a lack of pipelines to the prolific shale oil fields, and a shortage of refinery capacity in a state that already has the highest gasoline prices. Plus a Governor who aspires to run for President in 2028.

So California is now making an abrupt U-turn. Not only have the regulators been ordered to “work” with the refinery industry, but a new bill will look to boost oil and gas drilling.

How awkward!

Lastly, just as I was going to publish when the news broke that the UK is also looking at making a U-turn on oil and gas. Both the previous Conservative government(s) and the current Labour government were determined to kill the industry.

But that tune is changing. Reality collided with the prospect of losing large amounts of government taxes, high-paying blue-collar jobs, and a large domestic consumer for steel and machinery.

At the same time, oil and gas consumption has remained unchanged for the last 20+ years. The net effect is that the UK is forced to import ever larger amounts from overseas (with often far lower environmental or social standards) and draining foreign exchange reserves.

First, it was revealed that the UK North Sea holds far more oil and gas than previously thought, and should be sufficient to be enough to last until 2050. Now it looks like Labour will also make a U-turn in policy.

Even if California and the UK change policy now, it will likely take years to coax energy companies back. So this is all setting up for a very bullish medium to long-term outlook.

But should you dive in now? I’m not so sure.

I think the two big risks, at least in the short term, are OPEC and the US economy.

Starting with OPEC, they’ve been busy unwinding past production cuts. Forecasts of massive surpluses swelling inventories haven’t materialized, and have meant that oil all the bearish predictions of $50 oil, hasn’t come to pass (yet).

This is probably because of a combination of:

A) Most of OPEC was cheating like crazy, so the oil was already in the markets to begin with.

B) During the summer, the Gulf (and in particular, Saudi Arabia) burns over to 1mm bbl/d of oil for electricity, which reduces export capacity.

C) China has been voraciously gobbling up oil. The reason for China buying so much oil is hotly debated. Possibly their economy is doing better than people think, or that they’re stockpiling resources for an invasion of Taiwan down the road. Or it could be just opportunistic buying while the price is cheap (which they’ve shown to do in the past).

Either way, this fall will be the real test for OPEC supply. The Saudi’s will be able to ramp up exports, and it remains to be seen if China continues to buy.

As for the US economy, I have no idea anymore. The data has gotten so volatile that it’s hard to know what to believe. I don’t like to peddle in conspiracy theories, but I think that Elon’s DOGE layoffs did some serious (and lasting) damage to data collection at the BLS, EIA, etc.

And then there’s the “AI” capex boom, which is currently powering the US economy. Will the big tech companies continue to spend $500+ billion a year? I have no idea.

Just as an anecdote, I tried using Microsoft’s Copilot in Excel while working on this article. The data provider I use (Koyfin) exports dates as mm-dd-year, which Excel doesn’t recognize.

So I thought I’d try to use Copilot to re-order the dates to something Excel could recognize. After trying for over 5 minutes, Copilot gave up as it completely failed at the task.

Either “AI” has a long way to go, or it’s hundreds of billions of dollars that have been lit on fire with little to show for it.

If the US economy keeps humming along, all should be fine for energy. But if the US economy tips into a recession, it could be ugly.

Which is why I’m just going to sit, watch, and wait over the next couple of months. I already have a very large allocation to energy, both through my non-registered accounts as well as the Sleepy Portfolios. So I’ll likely wait until the end of this year before increasing my exposure.

But if you don’t have a weighting to energy, now might be a good time to put on some starter positions. Almost everyone is like me and worried about the next couple of months. Which probably means that it’s already fully priced into the market.

But if you do, I recommend buying the very highest of quality E&Ps (like CNQ or TOU), which can navigate through a downturn (if one materializes).

Energy investing is always volatile, but the next couple of months could be worse than normal (famous last words).

But once we get to 2026, I think things get a lot sunnier for oil and gas (assuming there isn’t a recession). We’ll have visibility both into US shale production trajectory and whether OPEC is a house of cards (or not). And the perception/sentiment of the energy industry will continue to shift.

So thanks for taking the time, and good luck out there.

Disclosure: I am long and have a beneficial interest in all of the above-mentioned securities. I may change my holdings at any time post-publication.

Disclaimer: This newsletter and/or any other articles that I publish should not be construed as investment advice. None of the strategies or securities mentioned should be considered as an investment recommendation to buy or sell. I am not an investment advisor, and I highly recommend that anyone considering this investment strategy or any of the securities first consult with a registered investment advisor to assess both the suitability and risk of any strategies or securities that are mentioned.